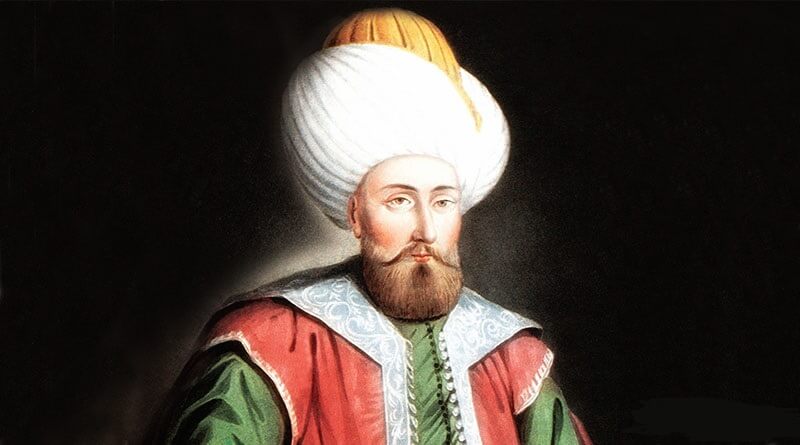

Osmanlı padişahlarından 1. Murat (Murat Hüdavendigar)’ın ingilizce hayat hikayesi, biyografisi, 1. Murat döneminin ingilizce tanıtımı.

1. Murat

1. Murat (Murat Hüdavendigar); (1328 -1389). Known as Hudavendigâr or Hünkâr, Murad succeeded his father but not without opposition from his three brothers, whose liquidation in 1363 is the first instance of the precautionary execution of relatives that was to become the normal practice at each accession. In both Anatolia and Europe advantage was taken of these dynastic disturbances by rival beyliks and by the Byzantines for the purpose of regaining some of the territories they had lost to the Ottomans. But their efforts were fruitless, and before the year was out Murad dominated the entire eastern bank of the Maritsa and had taken the great cities of Edirne (Adrianopolis) and Filibe.

Byzantium, now virtually isolated, was obliged to give recognition to all these conquests and even to agree to a military alliance with the Ottomans for operations in Anatolia. The chronology of the campaigns in southeastern Europe (hence-forth to be known as Rumili or Rumelia, the name given by the Turks to the area including Albania, Macedonia, and Thrace), as indeed the chronology of most events in early Ottoman history, is vague and confused, and we know little about the alliance among the Serbians, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Walachians, and Bosnians negotiated by Pope Urban V to meet the growing menace.

New Army : Janissaries

The alliance was defeated in the field at a battle on the banks of the Maritsa near Edirne (1365), and the Ottomans were hence-forth rarely to meet more than local opposition as they spread westward through Serbian Macedonia to the Vardar River and northward to the foothills of the Balkan Mountains. The capital was moved from Bursa to Edirne, indicating that any sense of insecurity in this foreign, Christian land that may have been previously felt had now been overcome. It is also possible that Murad was forced into this move, as he was into the creation of a standing army of non-Turkish Janissaries (Turkish Yeniçeri, “new army”), in order to counter the growing power of his own generals, who had been operating with heady success in almost total independence of him.

But Anatolia also offered prizes too tempting to be neglected. A dispute över the succession in a neighboring tribe that controlled the region north of Ankara up to the Black Sea permitted Murad to intervene in 1383-1384 on behalf of one of the pretenders.

He ultimately reduced him to vassalage, having secured his loyalty by a marriage alliance.

Another such alliance between Murad’s son Bayezid and the daughter of a neighboring Turkish ruler had already in 1381 brought the territories of Kütahya into the realm as the bride’s dowry. And in the following year the lands to the south of this acquisition were purchased from the Hamidoğlu. The frontiers of the Ottomans now faced those of the Karamanoğlu, a powerful beylik that had arisen in the southeast of Anatolia. When the inevitable trial of strength came in 1387, at a battle near Konya, it was the Karamanoğlu who were reduced to suing for peace. Ottoman power was now recognized as unchallengeable throughout the former domains of the Seljuks.

In 1388 the Ottomans launched a sudden attack on Bulgaria, at the conclusion of which the entire country was reduced to a province with its former king as a mere governor, and the Turkish armies were stretched along the Danube in strategic positions. In the summer of 1389 the army under the command of Murad himself, marched aeross Bulgaria and confronted the Balkan allies on the plain of Kosovo. The bloody encounter, legends of which stili live in Serbian folklore, ended in victory for the Ottomans, and with it the South Slavs all but disappear from history as a political entity for nearly flve centuries. Murad himself was assassinated by a Serbian prisoner immediately after the battle had ended.